News Reports

From:

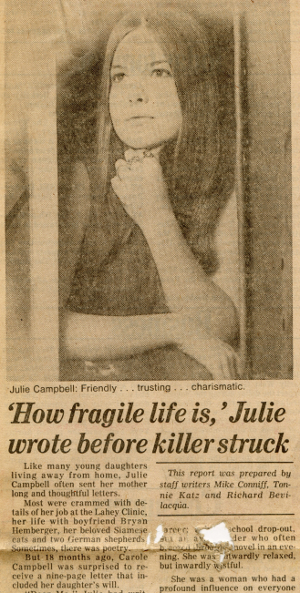

‘How fragile life is’, Julie wrote before killer struck

Boston Herald American, March 9, 1978

Like many young daughters living away from home, Julie Campbell often sent her mother long and thoughtful letters.

Most were crammed with details of her job at the Lahey Clinic, her life with boyfriend Bryan Hemberger, her beloved Siamese cats and two German shepherds. Sometimes, there was poetry.

But 18 months ago, Carole Campbell was surprised to receive a nine-page letter that included her daughter’s will.

“Dear Ma,” Julie had written, “The fact is that a schoolmate of mine from Lexington died recently … and it just got me thinking about how very fragile life is, how it can be snatched away so suddenly, without a warning, sometimes very unexpectedly.”

That letter is especially precious now. Nine days ago, 23-year old Julie Campbell was stabbed to death as she walked toward her home on Ellery Street in Cambridge. Police continue to seek leads to the apparently motiveless slaying.

According to her friends and relatives, Julie’s letter — which detailed her funeral plans and the wish that her organs be donated to charity — reflected the sensitive and independent spirit which set Julie apart from many of the young girls who frequent the Cambridge scene.

Beautiful and worldly, she was a complicated person: friendly and trusting of strangers, but so street-wary that she always carried chemical Mace; mature enough to leave home at 16, but too young and restless at 23 to settle down and marry or build a career; a high school drop-out who often breezed through a novel in an evening. She was outwardly relaxed, but inwardly wistful.

She was a woman who had a profound influence on everyone who knew her. “Julie was charismatic,” one close friend told the Herald American. “In a crowd of people, you’d be drawn to her.” Her death so upset her colleagues at the Lahey Clinic that many of them sought in-house psychological counseling to help cope with the experience.

But in many ways, Julie Campbell shared the lifestyle of the hundreds of young women who make Cambridge the center of their universe.

“She was just like 95 percent of the girls you see around here,” said George Lye, a long time friend who owns a Cambridge restaurant.

It is easy to find them on most days, long-haired and long-skirted young women who clerk in the boutiques, small shops and fast-food restaurants around Brattle and Boylston streets. In the evenings, they hang around the bars and restaurants which line Massachusetts Avenue up to Central Square. It is a close-knit neighborhood where jobs, drugs and friendships are instantly available.

The area is a magnet for young people who are trying to break away from home. Julie fled her home in Lexington six years ago when her parents’ marriage failed. “She chose not to live with either of us,” recalled her father Kenneth Campbell. “She dropped out of school before graduating and took a job waitressing at Hungry Charlie’s in Harvard Square.”

It was a turning point in Julie’s life. As a young girl, she had tested her independence by insisting on earning her own pocket money. When she was too young for a real job, she babysat for neighbors. Later, while she attended Lexington High School, she had a full-time job as a chambermaid at the Sheraton Lexington Motor Inn.

She didn’t need the money. Julie’s father, who now works for Raytheon, was then in the purchasing department at MIT. He provided well for his wife, two sons and two daughters; the family lived in a three-bedroom, ranch-style home with a swimming pool in the exclusive town northwest of Boston.

Howie Schofield, Julie’s high school guidance counselor, believes the teenage girl was driven by a determination not to depend on anyone. “She was definitely not one of the typical kids,” he said.

But in Cambridge, for the first time, Julie was truly on her own. She survived by working as a waitress in local restaurants. In one of them, she met George Lye, who got her a job in May 1973 at Zeke’s, a Boston coffee shop where he was the night manager. A few months later, Lye took a new position at Longley’s Coffee Shop around the corner from Hynes Auditorium. Julie followed him there.

The neighborhood was a tough one, frequented by drunks and prostitutes. Bob “Rebel” Key, the restaurant’s cook, said Julie was not aware of the powerful impression her waist-length auburn hair, light brown eyes and slim body made on the customers.

A few times after work, Key and Julie relaxed over drinks at the Newbury Steak House. Julie always ordered Amaretto over ice or a shot of Jack Daniels with a 7-Up chaser. Like the floor-length dresses she loved, the drinks were her signature.

Often, the evenings ended with serious discussions about Julie’s favorite subjects — politics, movies, and animals. She adored Jack Kennedy and was an old-movie buff, although her tastes ran the gamut from Clark Gable to Al Pacino.

She was dedicated to her dogs, Sibley, an attack-trained sliver German shepherd, and Circe, a black and tan of the same breed — and her two chocolate point Siamese cats, Oreo Cookie and Banana Man. Banana slept in the crook of her shoulder at night.

Soon, the company which owned both Zeke’s and Longley’s offered Julie a job in their management program. She was well-liked by her superiors, said Zeke’s manager Larry Van Liere, and had a reputation for being dependable and hard-working.

But Julie turned the offer down, preferring to try and pick up a few extra dollars moonlighting as a photographer’s model.

It was at the Martin Cornell Photo Studio in Boston that Julie met Bryan Hemberger, the slim, blond photographer with whom she lived for five years until just a few months before her death. The couple hit it off immediately — “that very first day we rode off into the sunset on my motorcycle,” Bryan said. “Jule left the bartender she was living with in Cambridge and moved in with me.” Their first apartment was on Commonwealth Avenue in the Back Bay.

The fact that Hemberger and Julie were sharing an apartment didn’t disturb her parents. In fact, Julie’s father and his second wife once lived across the street from the couple and saw them often.

“I’m not one of the parents that’s from the old school,” Ken Campbell insists. “My kids knew more when they were 12 than I knew at 25. Bryan took care of Julie — that was just their way of living.”

About two years ago, Hemberger and Julie moved to a three-room attic apartment at 9 Varney St. in Jamaica Plain, a rundown neighborhood of two- and three-story wood frame houses light years away from Julie’s well-to-do Lexington neighborhood. Bryan fixed the place up, putting in skylights, building counters in the kitchen and adding a tool room.

For a time, Julie was happy. The couple lived quietly “like a pair of old marrieds,” friends said. Said Al McDonough, a Boston policeman who lived across the street: “I’d come home from details at two or three in the morning and it was always quiet over there. Generally, said another neighbor, Michael O’Connor, the couple kept to themselves.

Julie spent most of her time at the Lahey Clinic, where she worked in the medical records department. She had taken the job in 1976 to help make ends meet when the Cornell studio moved to Florida and Bryan was out of a job.

Occasionally, she would spend an hour reading to visually handicapped women who lived nearby as a volunteer for the Community Service program of the Massachusetts Association for the Blind. She also did volunteer work at the Cambridge family planning clinic.

“About six months ago,” Bryan said, “Julie began to feel stifled and tied down.” The couple saw a family counselor for a while. But nothing helped. On Jan 8, they agreed to separate on a trial basis. Julie moved in with Jack Lavin and Claire Hutchinson, old friends who had a spare room in their Cambridge apartment. Bryan stayed in Jamaica Plain with the animals.

On Friday, Feb 24, Bryan and Julie met for a drink and belated Valentine’s Day celebration. She asked him for more time to think over her feelings and gave him a poem she had written. “What I want for you is what you did for me, to love each other enough to set the other free,” it read in part.

It was the last time Bryan saw her.

Three days later, minutes after saying good night to two friends outside a Cambridge bar, Julie Campbell was stabbed four times and left bleeding in a snowbank only yards from her home at 57 Ellery St.

At 1:45 a.m. on Feb 28 in the emergency room at Cambridge Hospital Julie Campbell died.

Night out ends in murder

Boston Herald American, February 28, 1978.

Julie T. Campbell said goodnight to two friends outside a Cambridge bar yesterday and minutes later, for reasons baffling the police, was brutally stabbed and left bleeding to death on the nearby street where she lived.

State Police Detective Lt. Thomas Spartichino said the murder of Miss Campbell, a 23-year-old medical records file cleark at Boston’s Lahey Clinic, was an “apparently motiveless crime.”

About 1 a.m., he said, she left the Plough and Stars bar at 912 Massachusetts Ave. with two friends, a man and a woman, and started walking alone to her home 57 Ellery St.

Twelve minutes later, Cambridge police received a call about a woman screaming outside 25 Ellery St., three-quarters of a mile from the Plough and Stars.

When Officers Thomas Case and Scott Stowers arrived at the scene, Julie Campbell, a striking blonde clad in dungarees, multicolored shirt and leather jacket, was lying between two snowbanks, bleeding profusely from the neck.

Despite efforts to save the young woman, she died at 1:45 a.m. in the emergency room of Cambridge Hospital.

An autopsy showed the cause of death was “a massive hemorrhage” resulting from several stab wounds, including one in the heart area. The autopsy was performed by Middlesex County Medical Examiner Dr. George Hori and State Pathologist Dr. George Katsis.

Spartichino, an investigator in the office of the Middlesex County District Attorney John J. Droney, said she appeared to have been stabbed four times in the neck, back, and chest, probably with a large hunting knife.

The knife wounds, the detective said, “are very similar” to those inflicted on two other murder victims, Carol Peterson and Paul Pschick, whose slayings three years ago in the same area are still unsolved.

Pschick, a 25-year-old bachelor, was stabbed to death the night of March 25, 1975, apparently by two men trying to rob him outside his apartment house at 29 Lee St. His screams routed the assailants, who fled in a taxi.

One week later, Carol Peterson, a 48-year-old assistant to a Harvard Business School dean, was murdered in the vestibule of her apartment house at 13A Ware St. She was stabbed repeatedly and robbed just before midnight.

Robbery, however, does not appear to be the motive in the latest Cambridge murder, Spartachino said. Miss Campbell was not carrying a pocketbook when she started her fateful walk home.

So far as police can determine she had spent the evening in the area of the Plough and Stargs but did not enter the bar with her two friends until shortly after midnight, according to bartender Dan Daly.

Daly said although it was the first time he ever saw the womain in the bar, he said he noticed her because she was “distinctive looking.”

A close friend of the victim, Bryan Hemberger, a 29-year-old photographer of 9 Varney St. Jamaica Plain, told a Herald American reporter he spoke on the telephone with her about 10 p.m. Sunday and “she was fine at that time.”

Hemberger said she moved from a Jamaica Plain apartment recently when the pipes froze and had been living with friends in Cambridge.

Miss Campbell worked at the Lahey Clinic for nearly two years. She formerly lived in Lexington and attended high school there.

Her father, Kenneth M. Campbell, lives in Acton and her mother, Carole, lives in Venice, Fla.

She also leaves two brothers, Clay and Bruce, both of Venice; a sister, Mrs. Lori Cotton of Venice; her maternal grandmother, Mrs Ruth Hebb of Venice, and her paternal grandparents, Mr. and Mrs. Kenneth Campbell of Coral Gables, Fla.